The architectural ensemble of the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius is not just one of the main religious centers of the Moscow region but a true gem of our cultural heritage. Pilgrims from all over the world, people of all faiths come here drawn to more than just the splendor of the temple complex. They seek the inspiration, the special atmosphere that prevails in the Lavra and its surroundings.

The spiritual component of Lavra’s appeal is pretty obvious. We would like to highlight its cultural component and show the educational impact that the museum collection had on various social groups.

Hundreds of people are frantically buying tickets to the Moscow exhibition of the famous Vatican Pinacoteca. But few people know that the Russian Orthodox Church has a similar museum — the Church-Archaeological Cabinet of the Moscow Theological Academy. Unlike the Pinacoteca that exclusively collects paintings, the museum presents handwritten and printed books, church items, graphics and relics, related to the lives of zealots of godliness and outstanding church figures.

In the Honored Guest Book, His Holiness Patriarch Alexy I wrote, “I visited the Church-Archaeological Cabinet many times… God willing, our students, applicants for the priesthood, will learn to love, understand and appreciate our true church art by studying this rich collection.”

In an interview with the chief curator of the museum’s exposition — Anna Yurieva Podkamennaya — we tried to find some answers about the role of the museum in the studies of the history and culture of our country. Especially since the museum is located in a historical building and is the largest church museum in Russia.

The Lavra and its monks took part in many historical events, and the temple complex itself is essentially an open-air museum. How does the museum help to study the history of our country?

The museum is engaged in a large range of activities and plays a significant role in the cultural life of the Church and society. It is located in the building of the Moscow Theological Academy (henceforth MTA), which was the first higher education institution in our country. At first, it was the Slavic-Greek-Latin Academy, one of its graduates was the famous Russian scientist M.V.Lomonosov. The MTA continues its legacy. As the successor of the Russian spiritual tradition, the MTA decided to organize a museum. At the time, the study of scientific archaeology was an important part of Russian educational science. In the third quarter of the 19th century, the Department of Church Archaeology was opened.

At the same time, F.I.Buslaev wrote his famous works: On the Influence of Christianity on the

Slavonic Language. Essays on the History of Language, a Case Study of the Ostromir Gospels — the legendary Church Slavonic manuscript, and Historical Anthology of the Church-Slavonic and Old Russian Languages. The scientist found out that the Christianization of language not only left its marks on the language forms but also influenced people’s intellectual development. In the Historical Anthology, Fyodor Ivanovich highlighted the diversity of genres and transformations of the prikaz literature and showed its influence on the formation of the literary language styles. Buslaev’s conclusions shaped further studies of the history of the Russian language.

During his research on iconography, Buslaev spent a lot of time working with archival documents, and he was able to demonstrate the underlying principles of image. He not only analyzed the external qualities of manuscripts and the technical details but also understood the symbolism, the style, and the overall look of the letters. After a lot of hard work, he eventually concluded that all images are based on some text. Hence the love and respect for the word in the Russian culture. It is exactly the verbal side of Russian art that the museum explores.

Actually, the museum is founded by the graduates of the Academy, the alma mater of the Russian patriarchs. Patriarch Alexy I (Simansky), Patriarch Pimen (Izvekov), Saint Filaret (Drozdov), Metropolitan of Moscow and Kolomna, famous for his correspondence in verse with Alexander Pushkin, and many other figures of the Russian Orthodox Church donated artifacts to the museum’s collection.

Were there any laypeople among the benefactors?

Yes, there were. We learned from archival documents that some of them were outstanding collectors, who were tolerated even in the Soviet times. It is known that the famous Kremlin doctor V. V. Velichko, for example, also contributed to the museum.

With the help of donor ledgers, we were able to identify about 200 bishops, including St. Luke (Voino-Yasenetsky), Archbishop Jerome (Zakharov), and Metropolitan Viktor (Svyatin), who headed the Russian-Japanese mission. Right now, we are trying to pull up archival records, and we find a lot of certificates of acknowledgment for people all across the world who had donated books and icons. Both the museum and the academy noted each donation with an acknowledgment: “Thank you for your contribution to the MTA Museum.” This is a great historical breadth.

In the Soviet era, the Lavra and the museum were used to demonstrate that the Soviet Union had no problems with the freedom of thought. Here is the Russian Orthodoxy, the services are being performed, there even is a museum of icons. It was a restricted area. The Lavra and, therefore, the museum, were the second stop for every foreign delegation.

Do foreign delegations visiting Russia today visit the museum as well?

Everyone who comes to the Lavra tries to visit the museum. We keep a guestbook in which visitors leave their suggestions, thank you notes, and feedback on what they’ve seen and heard. It contains autographs of Vladimir Putin, as well as many diplomats, public figures. Just this week, a representative of the Japanese Embassy with his wife has visited the museum. All

the guests sign the book. We try our best to convert the books to digital format and provide open access to the entries in the guest book, but it is rather time and labor-consuming.

I should mention, that the museum was opened to the public only 2 years ago. Before that, it was only possible to get inside on special request to the rector of the MTA.

Going back to the question of the museum collection and its historic role: as far as we know the collection was born twice, wasn’t it? Who was the founder of this tradition?

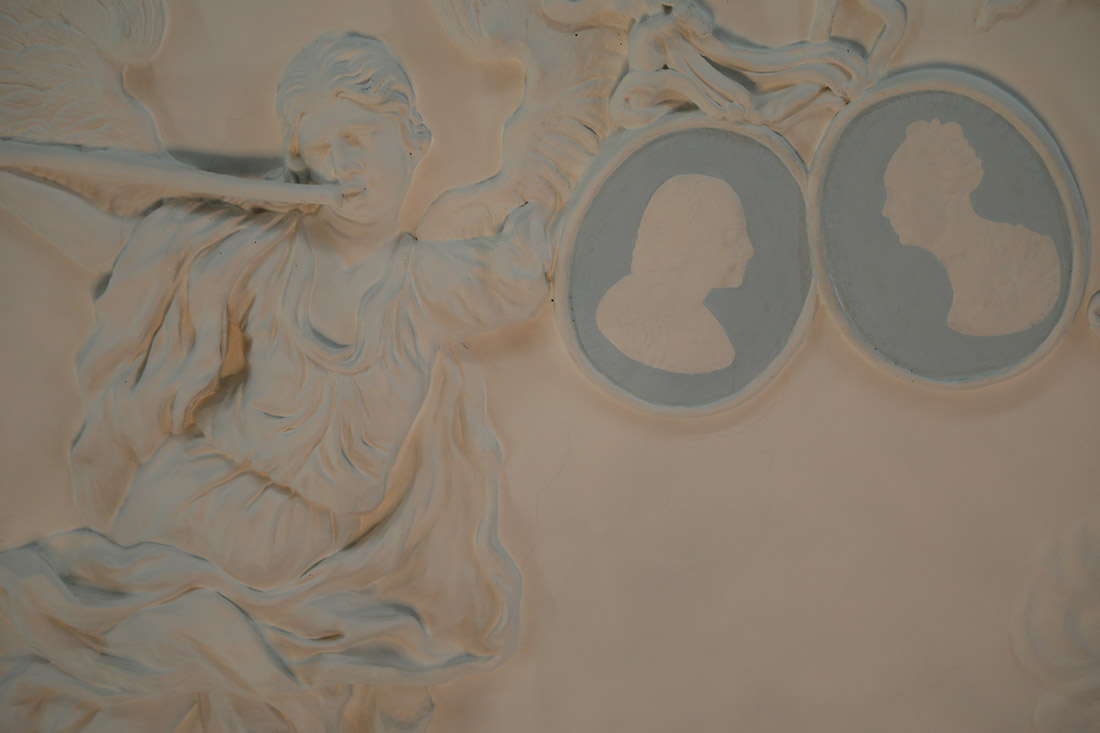

I must say that the collection’s history was indeed complicated. The first collection was built before the official foundation of the Church-Archaeological Cabinet in 1814 by the rector of the Academy, Archpriest Alexander Gorsky. There was an exhibition room in the library building that served educational purposes. A small collection of icons, paintings, and coins was gathered there. Meanwhile, in the Tsar Palace, where the museum is currently based, started the collection of royal gifts. The main collection at the original museum consisted of gifts from the royal family: portraits of emperors, members of the royal family, prominent religious and lay figures. Currently, this collection is represented in the museum by the works of the 18th and 19th-century artists.

After the revolution, the Academy was closed, and the museum was literally looted. To date, only a few exhibits have been found. Everyone thought that this was the end of the collection. But then a miracle happened. In 1943, there was a thaw in church-state relations, and in 1950, the museum restoration began.

Here we have the memorial office of Patriarch Alexy I, who was the head of the Russian Orthodox Church for a long time, he graduated from the Academy before the revolution. There is an invisible link between the past and the present – it was he who founded this school before the revolution. His cell was here. It is within these walls that his monastic life was determined. His personal belongings are also kept here, as well as his office decorations and furniture.

The personal and liturgical objects that once belonged to the head of the Russian Orthodox Church are now on display in the memorial office: icons from his cell, his robes, crosiers, mitres, panagias, crosses. In the Soviet era, at the critical moment in 1943, the building in Chisty Pereulok, where the German Ambassador once lived, was transferred to the Patriarchate. The German furniture was handed over to the Patriarch. Now his desk is kept in the museum. I would like to mention in particular one object that sums up the patriarch perfectly. He was very punctual and was always afraid of being late for some important event. But because of his beliefs, being a nobleman, he didn’t wear wristwatches. And the pocket watch was hard to get out of the many layers of his robes. So he often asked his assistants what time it was. One of the patriarch’s subdeacons (the future Metropolitan Pitirim (Nechaev)) gave him an unusual gift. It was a bishop’s staff, an integral part of the bishop’s life, a symbol of his power over the flock. In the middle of the staff, there was a built-in clock, so since that day, the patriarch had no trouble keeping track of time. Also, the patriarch had the boots that he wore his whole life, and he always cleaned them himself according to his assistants. One day his cell attendant cleaned his boots for him and was in big trouble for that.

Another showcase catches the eye with the unusual shapes of Coptic crosses. During visits to our country, the representative of the Coptic Church holds an unusual cross in his hands. And at the end of each visit, he hands it over to the head of our church. That’s how this unusual collection was built. The museum also houses more than 70 awards and medals, awarded to Patriarch Alexy by the church and the secular authorities during his years of service.

The historic interiors at the Royal Palace are of great interest. They survived the renovation in the 1740s when the building was prepared for Empress Elizabeth Petrovna. The reception halls are decorated with arch relief molding based on the drawings of Carlo Bartolomeo Rastrelli, mosaic parquet floors, and glazed tile stoves. In the stateroom, Elizabeth Petrovna implemented an idea by her father, Emperor Peter I: 32 cartouches depicting the battle history of the first Russian Emperor. As you can see, several eras are represented in the same space.

Today, society and school turn to the museum as a repository of human genius, the heart of culture in the transition from the past to the present. Do students of the Theological Academy conduct the excursions? Can we call them “museum teachers”?

For sure! In the most direct way. First of all, 7 years ago, the Department of Church Art History and Theory opened at the MTA. Here you can get a Master’s degree in museum studies and art history. Students defend theses on architecture, iconography, Old Russian and Western European art. Secondly, the work at the museum is considered the most respectable obedience, that is usually assigned to students of the second or third years. This obedience is a priority, you can even skip lessons to complete it. In addition, during the excursion, the guide has to share a lot of deep knowledge with the visitors because they often don’t know what are the books of the Bible and which one is based on which one. We have to make a long overview not just about icons but also about the basics of icon worship. Depending on the audience, we sometimes briefly retell almost the entire Bible. That’s why all the students appointed to obedience at the museum undergo mandatory training at the Guidance Department and take the exam. It’s a very demanding assignment.

So, museum education is directly related to the collection. The Guidance Counselor teaches weekly lessons to novice students. They practice public speaking for listeners of any level, learn to adapt the message to the audience. Some start working here as undergraduates and then stay, come to conduct excursions while studying for their master’s degree, some even design their own tours. Future museologists come here as interns and learn the general subject “Monuments description and analysis” by studying the collection directly. Here we have a place for doing master copies, so most MTA students go to the museum to study. You don’t have to leave the place, it’s very convenient.

Ancient icon-painting traditions at the Lavra have shaped the great art school. Masters of painting and mosaics were known even outside of Russia. Is the Academy currently training such masters?

The icon painting faculty has such a track. Students learn to make murals and mosaics, and we have the workshop in Sergiev Posad. For example, the mosaic decorations on the Lavra entrance gates were made by our students. But they mainly specialize in tempera painting, because one of the teachers here is a niece of the famous Mother Juliana (Sokolova). Mother Juliana restored the Academic Church of the Intercession in the MTA, the wall and arch

paintings, some icons at the festival tier of the icon-stand saved from the blown-up Moscow Church of Chariton the Confessor. Her works include the Refectory Church icon-stands, the Pavilion of the Three Relics painting on the former site of the St.Sergius’s cell. All this laid the groundwork for the tradition of teaching students in the Academy to paint in the style of the Moscow School of Painting. So they receive training in various techniques but mostly learn tempera painting.

Tempera is a technique of painting with a special painting medium. Mineral pigments, natural precious and semi-precious stones are ground into powder. It’s all done by hand. Ready-made mixes are also available, but our graduates can do it the old way. Grind the stones and prepare the emulsion. Egg yolk is used in different ways for different purposes. It is prepared in a particular manner, sometimes the recipe calls for garlic juice or vinegar. Then the binder is mixed with the pigment. This is called tempera (translated from the Latin temperare – to mix, moderate, soften).

The tradition preserves the canonical painting technique that had developed over the centuries. It is considered to be one of the strictest schools. Students do not go outside the Lavra unless necessary. It’s a city within a city. They move away from normal life for years of study. Every day they follow the order of academic life: prayer rule and obediences.

Since you’ve mentioned painting, are there any calligraphy relics in the collection?

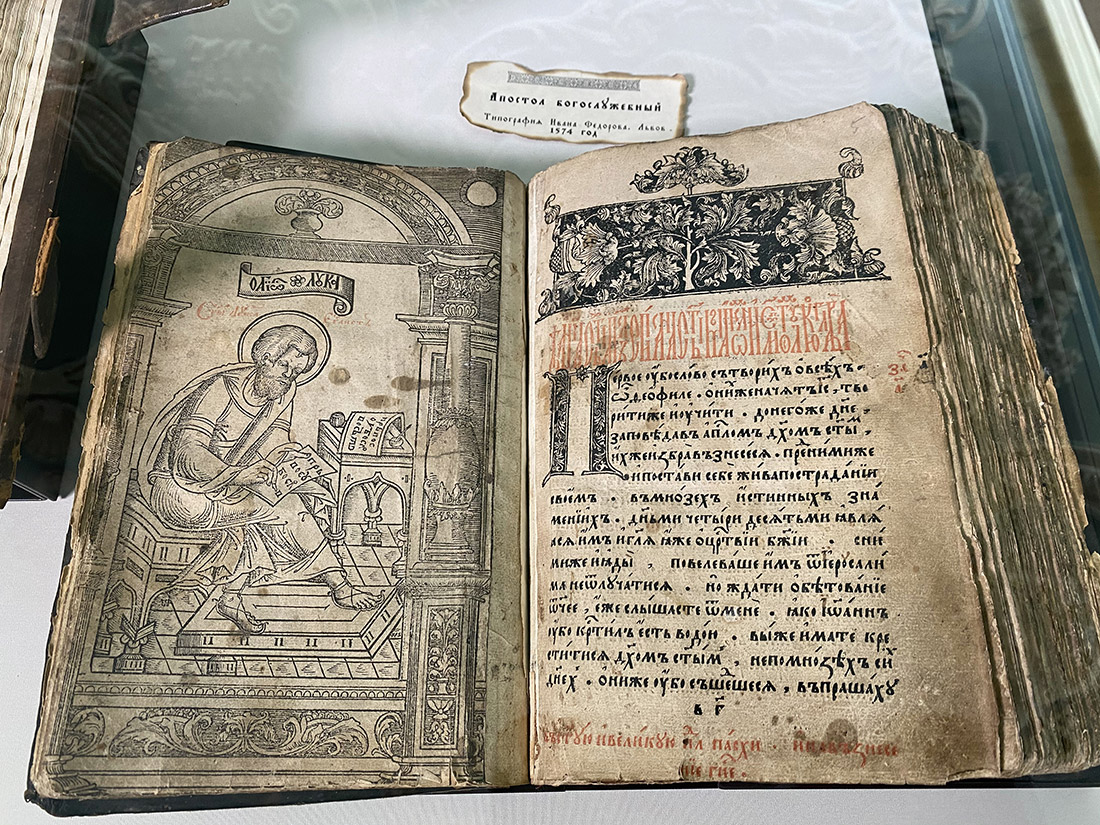

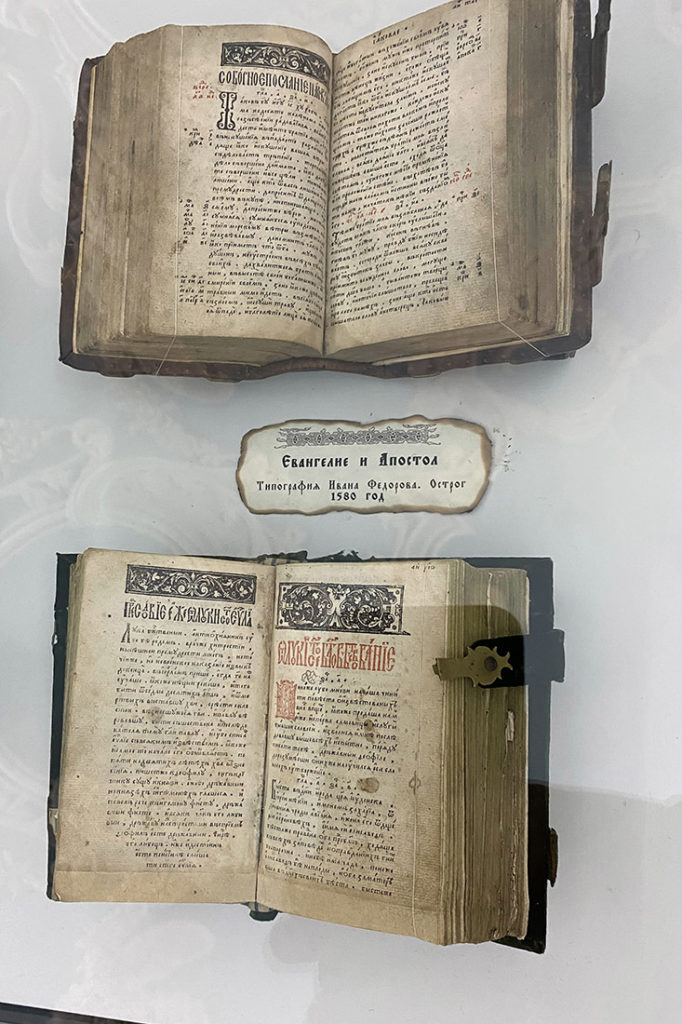

In the Soviet times, a lot of Egyptian papyri were brought to the museum, since it was originally an archaeological museum, we even have a few scrolls in Hebrew. Unfortunately, there are no birch-bark manuscripts in the collection. But most of the handwritten and old printed books were transferred to the MTA library after the fire in 1986. Today the museum holds the first printed books of Ivan Fedorov: the Moscow edition of the Apostol and the Ostrog Bible, and handwritten books dated 16th century – Irmologion (a collection of church chants), and the Gospel, that’s just the Russian books. In the Western European collection, we have an outstanding German Knights Armorial, the only other edition of that book is kept in the Munich Library. It contains more than 600 watercolor sketches of coats of arms of German knights, who fought in tournaments. The donator wished to remain anonymous. Another interesting item from our handwritten collection worth mentioning is the Breviary. It’s a Latin liturgical rite book written on parchment with watercolor.

We also have printed books of the early 20th century, for example, the Ordinary of Saint Nicholas (Kasatkin) of Japan. As we can see, almost 50% of the collection that has been preserved is memorabilia. In addition to artistic value, these items have a memorial value – they were once connected to the lives of famous zealots of godliness, hierarchs, and church figures.

The museum also holds outstanding paintings and full round sculptures.

For example, we have a famous miraculous statue by the Venetian sculptor Raffaello Romanelli. It has a very unusual story. This bronze statue of Jesus Christ, more than two-meter tall, was first kept in the Donskoy Monastery. In the middle of the 20th century, it started to attract many people. According to some sources, Blessed Matrona of Moscow sent people of faith to visit this statue, gather the rainwater from the hand of Christ, and according to

eyewitnesses, many were miraculously healed. The Soviet government could not accept this, so the statue was locked in the storerooms of the Shchusev State Museum of Architecture. And after a while, the Russian Orthodox Church started the long process of transferring the sculpture back. Only in the 80s they were able to return the relic. It was sold for four thousand three hundred rubles, and the money exchange was not allowed. So the director of the Shchusev Museum V.I.Baldin made a rather clever decision. He commissioned “a model of the Trinity Cathedral with the Nikon chapel and a model of the Solovetsky Monastery in the White Sea.” When, 10 years later, the sculpture took its place in the MTA museum collection, and art historians established that it was made by Romanelli, they noticed a surprising feature —Christ had the Western European type of face. The great-great-grandson of the Italian master said that “to get an order from the Russians, it was customary to make a person at an art piece look like the customer.” We can only confirm this because when the portrait of the great entrepreneur of the 20th century, Nikolay Karlovich von Meck by B.M.Kustodiev was found, the similarity was striking, not only the skulls but also the head structures and the postures were identical. For comparison, the collection includes other Italian sculptures depicting Christ, but they have a completely different, Semitic face. In addition, the red dots were noticed on the pre-master of the sculpture. This suggested that the sculpture was not only cast in bronze but also implemented in marble. Soon after this discovery, the marble twin of the art piece was found, it is installed at the grave of the Minister of Foreign Affairs in Georgia, USA.

One of the exhibition halls is devoted entirely to Western European art. Here we have works by German and Italian painters, dated as early as the 15th century, and we encourage visitors to find differences between icons and paintings. In the Russian Art section, you can enjoy the works by Surikov, Vasnetsov, Nesterov, Polenov, and other Russian artists. Some paintings are not even presented in the State Catalogue of the Museum Fund of Russia.

Is the museum engaged in science activities?

Yes, we are very pleased that this has gained momentum. Firstly, since the department was established, 40-50% of qualification theses are based on the museum collection. Last year, two of the defended master’s theses were related to the museum: a study on the liturgical tin vessels and a historiographic analysis of the collection’s history. As a result, new artists names were introduced to the scientific community, attributions were clarified, which is very important for us. The study analyzed the diary of one of the first directors of the museum. The main body of the collection was assembled during his years of work. This is Archpriest Alexey Ostapov, godson of Patriarch Alexy I (Simansky). He literally grew up in the patriarchal residence in Chisty Pereulok. His father, Daniel, was the patriarch’s cell attendant. They were very close to the Patriarch. In his diaries, Father Alexey describes his stay in the residence in a very reverent tone: “I visited His Holiness… Received this many icons, this many books from the Patriarchate…” He traveled from Sergiev Posad to Moscow as often as possible, several times a week, and brought donations and contributions to the collection. He was the head of the museum from 1955 until his death in 1975.

Another master’s thesis was dedicated to the Greek engravings from the collection of the Church-Archaeological Cabinet. We have an impressive graphics collection. Museum staff carry out extensive research.

How is the museum developing in the current conditions?

The restrictions, of course, had an impact on the museum, there was a quarantine, and the number of visitors decreased dramatically. There was even a period when we were closed. But you can’t stop the museum work. Our great advantage is that for the past 10 years our museum has been using the KAMIS museum information system, as did the Andrey Rublev Museum, the Historical State Museum, and other leading Russian museums. It allows you to work remotely on the registration and description of the exhibits, so all the museum keepers worked from home on shooting, attribution, and description of the collection. The museum inventory is now conducted on a new level, in compliance with the new requirements, it is improved with every step, getting closer and closer to the standards in this area.

Are there plans to visualize a digital museum collection?

My colleagues and I have been discussing this topic for a long time. We would love to make a project “the Heart of Russian Culture” based on our collection. We have developed a large number of quests and tours for the youth, our target audience. Through this project, young people will learn to appreciate the unique Russian culture. We interviewed people, studied the needs of the target audience, and learned a lot about what young people know and don’t know, what they are interested in. We would especially like for the project to gain more attention in light of our latest discoveries and attributions. This is our dream!

With St. Sergius’s help, of course. The last incident with the reverend’s sandals served as a special confirmation for us. Last year, the city of Samara requested the sandals for the exhibition. We were very concerned since the city is in a different climate zone, and the sandals have always been kept in the Lavra. We invited restoration artists, people who had opened the famous necropolis of the Ascension Monastery in the Moscow Kremlin, that is, people who knew what the leather of the 14th century looked like. They confirmed that the sandals dated the 14th century and took them for restoration. A miracle!

Does the collection of the Church and Archaeological Cabinet participate in field events and traveling exhibitions? Who is responsible for solving the internal issues in the museum?

We often organize traveling exhibits, but some artifacts are better not to take out. Seven centuries old leather is particularly sensitive to changes in the environment. In the case of the reverend’s sandals, our director did a great job: he found sponsors to make a special capsule for the sandals. It provides the constant humidity and the required microclimate.

The Church-Archaeological Cabinet is a collection of unmatched richness and cultural value, that contains more than 20 thousand items.

The official owner of the museum is the MTA. All internal issues – participation in exhibitions, repair, and restoration work – are supervised by the director Anton Sergeevich Novikov.